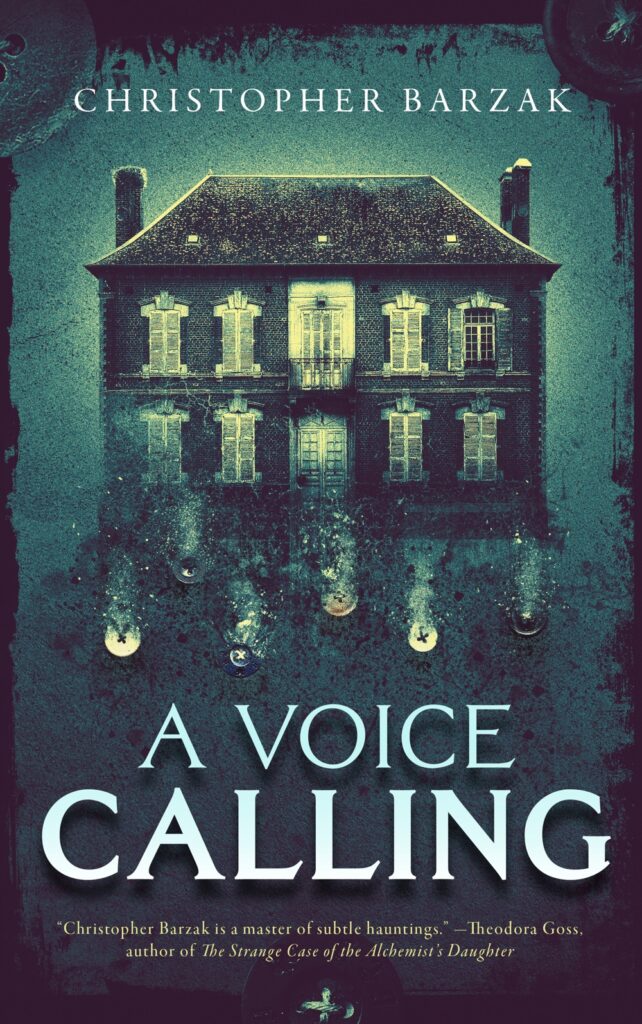

Christopher Barzak’s A Voice Calling is a novella about a haunted house; it is, more specifically, about the community haunted by the presence of a haunted house. The narrative voice, fascinatingly, is in the first person plural, which occasionally devolves into disagreements, collective selfishness, and arch judgment, much as a small town itself might. This is not a book overly concerned with being scary, or even particularly creepy, or weird; these are ghosts of existential sadness, mostly. The voice and these emotional resonances come through, but some missteps in expanding this novella from its initial form as a short story keep the book from delivering on its promise.

In a metafictionally Gothic flourish, Barzak opens the book with a dual acknowledgement of the weight of the past upon it, with an epigraph from one of Shirley Jackson’s greatest stories (“The house in itself was, even before anything had happened there, as lovely a thing as she had ever seen” from “A Visit”) and then moving immediately to a riff on Edith Wharton. Her “Afterward”, one of the classics of ghostly literature, begins “Oh, there is one, of course, but you’ll never know it”; the first chapter of A Voice Calling is titled “BUT IS THE HOUSE TRULY HAUNTED?” and the narrative itself opens “Of course the house is haunted.” It’s a touch too cute, too precious, especially in comparison with the weight of those works. (It doesn’t help that Kelly Link’s “Stone Animals”, a modern classic of the haunting mode, opens with a similar riff on Wharton). When it succeeds, the voice is the most interesting part of the book, with a folktaleish, self-aware bent that suits the plural voice: “We thought we’d been foolish all those years to think the house haunted. We shook our heads, laughing a little, thinking ourselves to be exactly what everyone who makes their homes in cities considers us: backwoods, superstitious, ignorant.” When it doesn’t, though, it just reminds you that this is a less successful work than the ones it’s riffing on, as in the nadir of an evil aunt saying “Bernadette, you must have water for brains. Oh, look at that, I just saw a goldfish swim past your eyeballs. Ha! Ha! Ha! A-ha! Ha! Ha!” Ha.. ha?

Where “Afterward” posits that a ghost is a tautology (“what in the world constitutes a ghost except the fact of its being known for one?”; “Stone Animals” does something similar with its “haunted” household items), A Voice Calling puts forth a different constitution of ghostliness: isolation. The first family to build and occupy the house, called the Blanks because their name is lost to history (again, a touch too cute), disappear one by one, “which is the same thing as dying if you think about it, for as long as no one you love can see or hear you, you might as well be a ghost.”

A Voice Calling traces out the history of its haunted Button House, from its mysterious founding through the succession of families that have lived there. The mysterious disappearances of the Blanks is the most interesting (and weirdest) story here. Their successors find themselves enmeshed in sleazy horror narratives replete with murder and incest, and the last family in a slightly more restrained Gothic melodrama. Barzak seems at times to be searching for the story he wants to tell vis a vis Button House. It’s noteworthy that this is the third iteration of the novella, which, per the afterword, he initially wrote 20+ years ago; when he failed to publish that novella he trimmed it down to the short story “What We Know About the Lost Families of — — House” (2007), lost the original novella, and then recreated it from his original notes for A Voice Calling.

I read the short story in the course of preparing this review; I regret to report that I find it a much more successful work. The differences become clear almost immediately; within the first paragraphs of each we find:

“What We Know About the Lost Families of — — House”: They turn on the shower and write names in the steam gathered on the mirror (never their own names, of course).

A Voice Calling: They turn on the shower and write letters in the steam gathered on the mirror (usually the letter “B” but sometimes a “Be” which seems appropriate given the existential circumstance of whoever writes these vague missives).

That “B” presages the stumbling block of the novella: by filling in the story’s blanks and interpretive spaces (indeed, “— — House” in the story becomes “Button House” in the novella), A Voice Calling dissipates much of the weirdness necessary for a haunted house story to, well, haunt. “Never their own names” becomes “B” becomes “Be” becomes Bernadette becomes the lengthy story of her being preyed upon by her button-factory-owning employer, whose country estate Button House is. It’s not that this new material is intrinsically bad or unconvincing, but it’s much too long and pulls the novella away from not only the interesting communal voice but also from the weirdness that is present in Button House.

There’s a tension here between Bernadette’s very unweird story, supernatural but explicable, and a vague, weirder element: here, an orchard predated the house; it’s where one of the Blank children disappeared, and there are brief hints that this force is using the house as some kind of lure or trap. The scenes involving the orchard are some of the strongest in the book; there’s a ghost of a stranger, more menacing work tangled in the roots of the apple trees. It perhaps barely needs to be said that the conclusion of the shorter work is much more muted and ambiguous. Where the book succeeds, it’s in emphasizing the holes in the historical record and the collective effort to bring attention where it’s needed: the Blanks, the apophatic ghosts that no one can see or hear, are where the story lies.

Zachary Gillan

Zachary Gillan (he/him) is a critic of weird fiction residing in Durham, North Carolina. He’s an editor at Ancillary Review of Books, the book reviewer for Seize The Press, and his work has appeared in Strange Horizons, Los Angeles Review of Books, Interzone, and Nightmare Magazine, among others. He can be found at doomsdayer.wordpress.com and @megapolisomancy.bsky.social