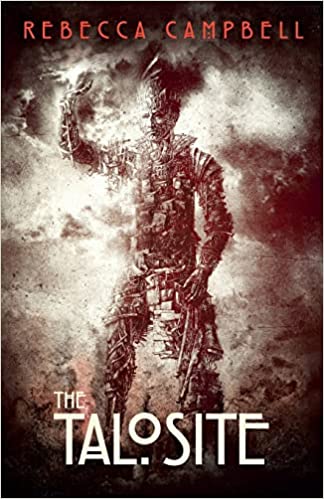

In 2022, small Canadian horror press Undertow Publications released two of my favourite books of the year: the unsettling, Cronenberg-esque Victorian body horror Helpmeet by Naben Ruthnum, and The Talosite by Rebecca Campbell, a science fiction/horror story in the tradition of Mary Shelley set in the mud, blood and trench laboratories of First World War France. The book is a dark love story of sorts, between Anne, a scientist who becomes obsessed with reanimating the fallen dead, and Ned, a soldier recruited into the military unit working for the secret government programme directing her. Rebecca was kind enough to join me for a chat about the book, war poetry, climate change and how society manipulates the dead.

Jonny Pickering: I really wanted to chat to you after reading your horrific alternate history of World War One, The Talosite. In his blurb for the book, Naben Ruthnum wrote that ‘The Talosite fixedly explores the unfathomability of both love and mass death’. How close does that get to encapsulating the themes you wanted to explore with this story?

Rebecca Campbell: It’s accurate! The story is about transformations, and about material afterlives. My academic work was about military commemoration, and I’m interested in how new things— a child, an idea, a community— can come out of disintegration and chaos. Love and death are both engines of transformation in the story— though they tend to smash things up before they make something new.

Two sections of the book stood out to me as expressing both the horror of WWI and the exploitation most people returned to once it was over. The first, where Anne remarks that a fellow scientist (unambitious, in her eyes) has “no sense of how far a body could be reshaped to serve other purposes”. The second where it is remarked upon that “these creatures would work in mines and factories when they were perfected, not storming about the country in breechclouts”. The reanimated dead are a speculative concept in your novella, but how much were they partly an allegory for how real people were viewed by the ruling class?

It’s SF and horror, but it’s mostly about how we use the dead. In our world, we might not revive them and enslave them, but we do put words in their mouths, ascribe judgments and actions to them, and redeploy them to support our institutions. In my story this exploitation is literal, of course. The dead aren’t just an inscription on a tombstone or an excuse to do something horrible in their name, they’re a physical presence exploited by violent states and empires.

And, as you say, this isn’t much different from how all of us are perceived under capitalism: parts in a machine, rather than subjects. We still imagine people and animals and ecologies in those instrumental terms. It’s also not that different from how prisoner-conscripts are being used in Ukraine right now.

I’m interested in material afterlives, and the way our current self is just one stage of matter, a temporary state that is part of an ongoing series of transformations, rather than a singular form. Also, the way we’re composite entities. This is literal, in the sense that we’re covered in micro-organisms, and our gut microbiome has a huge influence on who we are and what we feel. But it’s also true in the larger sense: we are a part of what we meet, who we touch, who touches us. We’re one temporary resting point for a huge archive that spans generations and species and communities. I find that incredibly moving and beautiful. But it’s also good for horror.

In The Talosite, any possibility of freedom and change comes when creatures connect to one another, and to living humans, independent of the institutional structures that entrap them. It comes from recognizing that the dead aren’t passive automatons, but a new kind of subject, a new way of being in a changed world.

It’s a book heavily influenced by Greek mythology, as well as those classic authors who blurred the lines between science fiction and horror, most noticeably Mary Shelley and Lovecraft. How much direct influence did you take from those classics, and what are some of the other, perhaps less apparent, influences on the book?

Poetry was probably the other big influence on The Talosite— not so much in the language, as the subject matter. I worked on war literature all through grad school, and I read all the trench poetry I could find published by Canadian veterans of the First World War. The texture of the world is very much drawn from that material— it’s literary poetry, but it’s viscerally horrifying, and describes bodies and earth blending into a kind of morass, where distinctions (living/dead, us/them, earth/body) are lost. I also looked at a lot of war art, and saw the same loss of distinction, but rendered in oil paintings of no-man’s-land, where dead men and dead horses and fallen trees are destroyed and recombined and destroyed again. I listened to early recordings of bombardments, skits written and performed by soldiers, brief accounts of their experiences, songs they sang.

And I’ve read much of the First World War canon in fiction and memoir: novels like Generals Die In Bed describe the total, sensory disorientation of the front, and memoirs like Goodbye to All That describe its disorienting absurdity. It all contributed to my work on The Talosite.

Beyond The Talosite, your other writing often focuses on climate change. What I like about your climate fiction is its focus not just on the climate itself, but how it will affect people and how we relate to society, not in any immediate apocalypse, but as a series of long drawn-out catastrophes. What is it about climate change in particular that compels you to write about it, and how hopeful are you that humanity can avoid its catastrophic long term effects?

I write about climate change because I’m terrified of climate change. Stories like Arboreality (from Stelliform Press in 2022) and “The Bletted Woman” (that one was in F&SF a few years ago) have helped me understand my own grief, anxiety, and all the other complicated feelings that come with living now. My character is pretty gloomy, so I don’t tend toward hope about the future, but my grimness doesn’t mean surrender, exactly. We’ve changed in the past, and I hope we can change again. And I don’t mean just changing our actions but the way we think about our relationship to the world and other people. Mostly because justice is necessarily central to any discussion of climate change.

But… if there’s one thing science fiction and horror stories offer, it’s a way to think on a larger scale than the every day— to approach something huge and sublime and transforming. I need that now, since climate change is so much larger than anything I can grasp. Writing stories about massive, interconnected communities helps me think beyond myself, and I need that right now.

I mentioned Naben Ruthnum already, but both The Talosite and Ruthnum’s body horror novella Helpmeet made the Stoker Awards preliminary ballot this year, and both were published by one of my favourite presses, Undertow. In my opinion at least, a lot of the best horror is coming out of small presses at the moment; do you have any favourite small press fiction, and what do you think of the general role small presses play in putting out a lot of the weirder stuff the bigger publishers might be wary of?

Okay, first, Undertow is brilliant, and I hope everyone goes out and buys Helpmeet, which unsettled me so much, I had to look away while I was reading. That is obviously a high compliment when it comes to horror.

And yes about small presses and horror. I wonder how much of that is about editorial taste. Small presses are so much driven by one person’s vision, and maybe that can be more distinctive than a large organization that has to satisfy a lot of people? If you read an Undertow book, you know you’re going to get Michael Kelly’s perspective on what’s interesting in weird fiction and horror, just like you’re going to get Vince Haig’s designs. Same with Lethe. And it applies to magazines— I think about Bourbon Penn or Apex, and how you know you’ll get something creepy, but also unusual, something that challenges our expectations for the genre.

I feel lucky to be published by small presses driven by this kind of vision. Things get weird over here.

Finally, are you working on anything new we can look forward to? More climate fiction, or searing critiques of European imperialism in the works?

Always climate change fiction, as an ongoing attempt to manage my own anxiety. And probably more First World War stuff. It’s subject matter I’ve approached in fiction, in academic writing, as a reader and a critic. I don’t think I’ll ever really leave it behind.

And body horror. Because I’m curious about the limits of the subject, and where we touch other people and animals and ecosystems. Body horror is a way to examine those points of contact and conflict and transformation.

So: all things sad and/or gross. And metamorphosis. And our relationship with landscape and community.

Thanks so much Rebecca, it’s been great to have you here.

Thank you for reading!

Rebecca Campbell

Rebecca Campbell is a Canadian writer of weird stories and climate change fiction. Her work has appeared in The Year’s Best Science Fiction, The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, and The Best Science Fiction of the Year, in addition to magazines including The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Clarkesworld, and Interzone. Undertow Publications published her novella The Talosite in 2022, and Stelliform Press published her novella Arboreality the same year. She won the Sunburst Award for short fiction in 2020, and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award in 2021. Her Work has also been nominated for the Aurora Award and the Philip K. Dick Award. You can find her online at whereishere.ca.