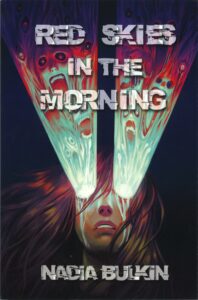

The internet abounds with comparisons, joking or not, between Covid and zombie movies; people would deny zombies are real even while they’re being eaten, your neighbors and acquaintances have revealed that they’re the type to hide that they’ve been bitten. Others compare the inefficiency of the government’s response to Covid-19 to societal collapse in zombie apocalypse fiction, reactionaries flip the comparison and warn that vaccines might zombify people. Whether uncomfortably accurate or absurdly insulting, there’s an obvious link to be made between fictional zombie pandemics and our real-world catastrophe. It’s one that Nadia Bulkin toys with in her new novella Red Skies in the Morning, from the consistently-excellent micropress Dim Shores, but not in the way you might think.

The novum of the book is not zombies but paracontagions: hauntings which move from a “shell” (typically videos or polaroids) to a human target, causing their bloody death exactly a week later (the body horror of the premise surfaces rarely, but to incredibly disturbing effect when it does) – unless someone else assumes their bond. The book’s protagonist Selene lives with her younger sister Hannah, who she raised after their parents died, and when Hannah goes missing, Selene assumes she’s been bonded to a paracontagion and has seven days to live, which gives the narrative the compelling sense of shape and propulsion of a thriller.

Told in tight third person, plain and unornamented prose, Bulkin shines at conveying the interiority of her characters, although her sentences do sometimes feel like they’re tumbling over themselves in conveying too much, too plainly (eg “There was nothing worth chasing down in her messages she’d received following her post about Hannah being missing”). This interiority strengthens the most interesting thematic angle of the novella: a dualism of thought and ontology, splintering and arguing reactions to such a historical rupture. Selene works for the federal government as a pather, someone who helps the infected find a volunteer to assume the paracontagion bond, and the novella is thematically saturated with self-sacrifice, communalism, and approaches to mutual aid that our age of disasters calls for – not for nothing is the bond with the paracontagion what is repeatedly emphasized. On the other hand of this philosophical divide, there is selfishness, victim-blaming, a rising tide of fascism.

Bulkin once wrote an essay “In Defense of the Price” – focused on movies, but the principle applies here as well – about the narrative necessity, in horror, for characters paying the price for meddling with (or even inadvertently seeing) powers evil or otherworldly, but also “about that great price we all must pay for being alive, being human, being part of a cruel civilization” built on exploitation and violence. It feels sometimes like we’re all paying that price now in what we call the post-Covid world, even though there’s no such thing – Covid is part of the world now because people in positions of power chose not to prioritize saving lives, but to keep the economic engine of capitalism grinding to bring prosperity to the 1%, offloading safety from societal protections to individual choices. In Red Skies in the Morning the government is putting in a bit more effort, but the price is there to be paid nonetheless.

Work, of course, grinds on, even in the face of paracontagions randomly wiping people out, and it still sucks: Some people rely on the compensation paid by the government to pathing volunteers as a side gig, risking their lives for a pittance; a pathing agent drinks himself to death after exhaustion and overwork leads him to a mistake that kills a boy who should have been saved. It doesn’t feel like a coincidence that Selene worries about Hannah being “psychically shackled to a monster” in the midst of a conversation with her boss. Selene finds herself torn between the vastly different ontologies of Hannah (“Hannah-logic,” as Selene frustratedly refers to her un-rational thought, a “grand naivete” in approaching the world) and the federal government. Pathing agents are forbidden from engaging emotionally with their projects, from thinking of them as people rather than as cases. Selene, internalizing that, struggles with emotionality, and constantly defaults to the overly-rational, bureaucratized language of her workplace. “If I had known your paracontagion detachment was incomplete…” she starts to tell one young woman, consigned by her mother to a mental hospital (called Bellevue, after the notorious NYC institution; the book takes place in Ponte City, which appears to be named after a South African highrise-turned-disaster-symbol). “Again with these fucking words that don’t mean anything! He’s a ghost, you dense bitch, they’re all ghosts!” the woman interrupts.

Ghost, here, is a forbidden word, an un-rational response to something the government and some facets of society are trying desperately to rationalize (government scientists, Selene has to remind herself at one point, had “never confirmed that paracontagions were indeed the spiritual remnants of deceased human beings”). “Paracontagion mitigation 101” is to not look at things too closely – both literally because that’s how you get bonded to a paracontagion shell, and metaphorically because it’s easier to avoid thinking about the shitty state of the world. People argue about what increases in viral numbers mean, what society should do in the face of such a disaster, how to discuss ghosts or hauntings or paracontagions. Teens unite behind a hippie-dippie group called Rock the Horizon (the horizon of the “white space between life and death. The door that we’ve shut. Just like we’ve sealed away everything else that makes us uncomfortable.”), using kept ghosts as therapeutic machinery, while suburban parents rally under the fascist banner of the Bluejay Society. Others espouse a Ligottian antinatalism, contrasted with Selene’s selfless parenting of her sister.

This societal bedlam brings us back to zombies: here, it’s a pejorative term for “Brainless leeches taking up space in the world,” used to dismiss the victims of paracontagions, in addition to society’s other undesirables. “Zombies” are being picked off by a serial killer, the blandly-named “Video Man,” for his use of haunted videos as a murder weapon (he is the novella’s weak point, not fleshed out as well as the sisters despite being prime narrative mover of the piece). Selene dwells at one point on the tautological nature of these pessimistic ontologies and the dismissal of zombies – people are useless zombies because paracontagions or Video Man kills them; Video Man or paracontagions kill them because they’re zombies. Hannah, on the other hand, with her Hannah-Logic, is philosophically devoted to one thing: “I don’t think anyone’s a zombie.” That’s the core message of Red Skies in the Morning: the philosophical devotion to humanity, to the value of human life, in the face of mass indifference and cruelty; to being willing to pay the price even at great personal cost.

Zachary Gillan

Zachary Gillan (he/him) is a critic of weird fiction residing in Durham, North Carolina. He’s an editor at Ancillary Review of Books, the book reviewer for Seize The Press, and his work has appeared in Strange Horizons, Los Angeles Review of Books, Interzone, and Nightmare Magazine, among others. He can be found at doomsdayer.wordpress.com and @megapolisomancy.bsky.social