Several waystations were confirmed lost, their final moments recorded by radio in a blast of static. Sometimes the loss was dramatic, broken and nigh incomprehensible voices going silent in the middle of a detailed warning. Other times the loss was quiet, an operator stepping away to refresh their coffee and simply never returning, the conversation they were a part of now forever incomplete.

It was my job as a betweener to follow the stone-paved path and check on the waystations, both those that were lost and those still fully functional. I traveled with a cart of emergency supplies, as well as various entertainments to trade out with the operators, acting as a lending library to those starved for distraction, both from their own thoughts and from the encroachment. The operators were often pathetically glad to see me, offering up hoarded treasures, like a small cup of espresso with a dollop of honey and cream or one of their few pseudo-steaks or even, more rarely, an illegal memento from the encroachment itself. These mementos were always small, seemingly innocuous things—strange-colored rocks or shards of bone or a fragment of a broken machine—but they still had that aura of the forbidden about them. I refused those gifts if I could do so without causing offence, but if not, I buried the mementos along the edge of the encroachment, six feet down. For hours afterward, the spots where the memento touched my skin would tingle, the flesh subtly darker as though from a mostly-healed bruise.

I had a lot of contact with the encroachment, but I never felt like I knew it. Or that it knew me. But that’s what the operators told me, in different words and with different inflections, all repeating the same essential premise: the encroachment knew them.

The encroachment wasn’t anything noticeable in the landscape, not that you could see. Operators sometimes claimed they saw evidence of it, squiggling lines in the dirt or the air that grew clearer when seen from the corner of the eyes. But for most people, the encroachment was defined by the path. Ten feet from the edge of the path, the encroachment began. That was the reason waystations were long and narrow, and why they were built on both sides of the path, a covered walkway and gate set between them. All of that provided the illusion of space. By policy, waystations didn’t even have windows facing the encroachment.

I asked my dispatch supervisor about that once. Toma shook her head, just shook it like a dog, real quick and brittle-like. After staring at her desk for a full minute, the fingers of her right hand tapping the surface like she was crushing a crowd of ants, she said, “Well, once the glass clouded with red mold and when it woke—”

At least I think that’s what she said before she cut herself off. When I asked her to repeat herself, she handed me my schedule and said, “Memorize the route.”

My boots clopped along the stone path. The path stretched out before me and behind me as far as I could see which, according to various studies, was only about a hundred yards despite the path seeming to continue on to the hazy gray horizon. Memorization was required of each of us who walked the paths. We were told it was a matter of life or death (or being lost and being found, depending on the mood and sense of humor of the speaker). But memorization was pointless since there was only one path and, while walking it, that path always seemed straight.

And straight ahead was the first waystation on my list. Waystation Bronchial.

The walls were painted black while bright red, yellow, and blue pennants of cloth hung from haphazardly mounted poles. In some ways, it looked like an abstraction of a fireworks explosion. Pink flamingos decorated the dirt lawn, their eyes glowing with battery-powered lights. Even though the sky was a clear blue above the path, sunlight near the encroachment always felt a little weak, like watery tea.

“Roget?”

I called out the operator’s name as I reached the edge of the waystation. Cameras perched on the corners of the building, but it was a toss-up as to whether they were working. When I first started, I had operators pull guns on me, tackle me to the ground, or run screaming into the encroachment from an overly cheery hello. I’ve since learned to play it safe and slow.

“Anyone home?” I asked. The air was full of weight, a pressure on my eardrums.

“This isn’t anyone’s home,” Roget said. “But I’m here, if that’s what you’re asking.”

He stood behind the waystation’s gate. I’d missed him on my approach, perhaps because he was standing so still, the only motion the steam rising from the mug awkwardly cradled in one hand. The other hand was bandaged, dark with either blood or dirt. His eyes were equally dark and unwelcoming.

Roget was always taciturn, but hostility was unusual for any operator. People chose this job because they were okay with being alone, but being alone and being alone in the encroachment were two very different things.

The thing is, operators appreciated betweeners. They looked forward to the distraction, if nothing else. I pulled the small supply cart up alongside me, but Roget’s expression didn’t change. He didn’t offer me espresso, with or without cream and honey, or any sort of gift. Still, I went through the obligatory motions.

“All stocked up?” I asked, and he nodded.

“Need anything? I asked, and he shook his head.

The door on the right-hand side of the waystation was boarded up. Roget noticed my look, but didn’t offer to explain. As a betweener, my job was overtly to bring supplies and entertainment, but covertly I was supposed to keep tabs on the operators. After each walk of the path, I spent my days writing reports on each operator, sitting in on psychological evaluations of those reports, and making suggestions for how to help operators weather the encroachment.

Roget was rarely mentioned in my reports. His waystation was in the shallows. The deeper one walked on the path, the more the miasma, for lack of a better word, was felt. The waystation at the end of the path had it the worst. Though they were equally distant from an edge as Roget, the encroachment’s effect was directional and the path was one-way.

But here was Roget’s bandaged hand and a boarded-up door. That right-hand half of the waystation was more decrepit, too, black paint peeling like burned skin where the paint was fresh on the left-hand side. The pennants on the right were faded, their ends shredded as if by wind, though the air rarely moved along the path. Roget’s gaze was flat. Still, I had to try.

“So, I’ve heard some strange things.”

Roget stared.

“Some waystations are off the air.”

“They are,” he said, and I couldn’t tell if it was a statement or a question.

“But you haven’t noticed anything?”

He shook his head. He stepped back from the gate, opening it as he did so.

“Thanks for stopping by,” he said.

I walked through the gate with the cart in tow. As I moved by Roget, a strong smell flooded my nose, though I couldn’t tell if it was coming from him or the boarded-up door. It was rot, sweet and caustic. I almost gagged. The mug in Roget’s hand steamed, the liquid inside just under the lip, as full as if he’d never taken a sip, and that steam veiled his face.

As I continued on my way, I looked back at Waystation Bronchial every so often. Roget never moved and the gate remained open. I was glad I didn’t have to come back that way. Usually, I felt sympathy for the operators—it wasn’t an easy job—and though Roget had never exactly been friendly, he’d never been like this, either. I shivered. It was the first time I felt glad to be alone on the path, just me and whatever was held at bay on either side.

***

Sometimes friends on the outside asked me about the job. Not what I was doing or whether I liked it or not. They wanted to know the why of it. Why have the waystations out there at all?

I answered the way I’m supposed to, bringing up scientific research and how studying the unknown often brings unexpected benefits to all parts of society. I used the Antarctic research stations as examples. The various space flights and trips to the Moon.

And while that’s true, I didn’t mention the equally important and unpublicized reason for the waystations, which was that occasionally people emerged from the encroachment. People who went missing decades ago. People who were ghosts, no record of their existence in any government database. Or people who were on official records, but who already existed elsewhere in the world, these new strangers their doppelgängers.

Which was to say nothing of what else has been found, which was hushed up even in-house.

***

It was a few hours to my next stop, Waystation Ventricular, the first of the waystations that had gone silent. I tried to keep myself from dwelling on that silence. The more unsettled your mind was, the worse a time you’d have walking the path.

As a betweener, you developed a sort of immunity to the encroachment. Not the thing itself—I wasn’t sure there was any sort of immunity for that—but for the dread it could lay on you. Some operators talked about that with me, how the encroachment was like that guy who always stared at them on the bus. Didn’t do anything else, just stared, but still the menace was there.

I could always hear Waystation Ventricular long before I saw it. The operator, a woman named Illia, arranged speakers around the outside of the waystation and had music going nonstop. Generally some sort of drum and bass or electropop where, for the longest time, all you can hear is the bass like the heartbeat of the ground underfoot before the higher notes kick in and there you are at the waystation, Illia out on her lounge chair with a drink in hand, her notebook open, pages all blank.

There was no warning this time. Waystation Ventricular appeared ahead, still holding the shape and paint it was built with. Illia didn’t care about appearances because the world was given shape by what she heard. As much as I was friends with any of the operators, I was friends with Illia, although I think she was friends with everyone. Though I’d been worried when her station had been listed as lost, I’d kept that worry out of my mind. If it was the encroachment, there was nothing I could do until I got to the waystation, and even then…

No music meant something was seriously wrong.

I stopped the cart and removed a pistol from it, inserting the magazine like I’d been trained, and leaving the safety on, like I’d also been trained. This was that sort of last-ditch emergency we’d been assured would never happen, but which every betweener feared. There had been times when the path was too quiet, with both the atmosphere and temperature of a walk-in freezer, and I’d been convinced that it was the end for me.

But those terrors had always ended up products of my mind, the fear paralyzing but baseless. What I felt now was dread, the inevitable settling in my stomach. I wanted the gun to be a solution, but I knew that if I needed the gun, it was already too late.

The waystation’s gate was open. The doors, too. I heard the buzzing of flies, but saw no flies. The air smelled faintly of sewage. I stood between the two open doors and forced myself to look inside one and then the other, expecting to have to turn away in horror and disgust.

But there was nothing. Through the left-hand door I found the empty kitchen, dirty plates littering the small table. The bedroom was messy, but that, too, was normal. Across the path in the right-hand half of the waystation designated for work, I followed the buzzing to the radio. Up close, it still sounded like flies even though I knew it was static. I flipped the channel to home and radioed my position.

“Where is the operator?” Toma asked. I could tell by her voice she sensed something in mine.

“The operator is absent.” I struggled to keep my thoughts mechanical and factual. “Waystation in good condition.”

There was a pause, and then Toma’s voice grew concerned. “Are you still on the path?”

“Yes, of course,” I replied, but her question made me doubt myself. I looked around, but everything seemed normal. “I’m on the path.”

“Understood,” she replied. “Be safe.”

That note of care almost broke me. I focused on the smell, which was stronger here, following it to a spot on the floor where the concrete was mottled, like there was a shadow there, but nothing to cast it. The smell wasn’t strong enough to be nauseating. Standing close to the dark spot, I thought I could hear something else, now that the radio had been silenced.

I closed my eyes and held my breath.

There was a tiny wisp of an electronic beat, the kind of music Illia loved. I couldn’t tell if it was a memory or if I was actually hearing it. I lingered, hoping, and then I heard Illia’s voice right next to my ear, Leave me.

I grabbed my cart and abandoned the waystation. I felt I was being watched the entire time, and the watcher wasn’t friendly. A child’s fear filled my stomach, that particular kind where if the fear is acknowledged, it becomes real, the monster reaches out from under the bed or pulls you into the open closet. Illia was gone, and I wanted to be gone, too.

***

A half hour later, when the fear had dissipated, I stopped to eat. As I rummaged through the cooler containing sandwiches and an energy drink, I found a clump of mud, like something that would be flung off a shoe during a rainy day. Maybe it had been overlooked when the cart was cleaned or it fell in while I was loading supplies.

But when I touched it, even before the clump shifted color in the light from brown to a deep oily blue and back again, I knew it was a memento. I dropped it back into the cart, my hunger forgotten, every muscle tense with a sense that the world wasn’t real and if I looked just a bit too hard at my surroundings, they would tear like wet paper.

I should’ve buried it immediately, like I’d done with every other memento I’d been given. But when I picked it up again, using the sleeve of my shirt to keep from exposing myself to it directly, I sensed something that shocked me. Friendliness. As if Illia had slipped it into the cart while I was searching her waystation.

I turned the clump of mud to reveal half a thumbprint embedded in one side. On the other side, a fingernail had dug in to create a crescent moon. Both marks were surely a result of chance, but they hit me with extraordinary meaning, and I felt I was falling victim to the encroachment through the memento, as I’d been warned about countless times. I drew back my hand to throw the clump far off the path.

But I couldn’t do it.

It was my only connection to Illia.

It made no sense, and I can’t explain my conviction. Not to myself, not to Toma, not to anyone. Instead of throwing it away or putting it back into the cart, I put the memento in my pocket. I did not eat my sandwich. I downed the energy drink. I walked the path.

***

Waystations Vertebral and Osteal were empty. Hulla at Waystation Tarsal wouldn’t open their door, simply telling me I shouldn’t worry, everything was fine, and I should just move on. Their voice was soft, like melting ice cream. The waystation had gone silent, but Hulla was there. I left a care package of treats and medicine and promised someone else would be by in a few days.

Waystation Cranial was simply gone.

I stood in the middle of where it should be, afraid to leave the safety of the path. Maybe the encroachment had moved? I didn’t want to chance it.

From the edge of the path, I inspected the ground. There was no evidence the waystation had ever been where the map said it was. Numen, Cranial’s operator, was always quick with a joke and a shot of homebrewed liquor. They never needed a thing from the cart, but our brief contacts were bright spots in both our work days.

“Cranial’s gone,” I radioed back to Toma.

She hmmmed. I could hear her typing.

“They’re still broadcasting. Cranial’s fine.”

“No, the waystation is gone, Toma. It’s not here.”

“Cranial is not an issue. Proceed to the next waystation on the list.”

As ordered, I continued walking the path. I refused to think about what I was leaving behind.

***

I wondered what the waystations were broadcasting. Only the operators and the supervisors knew. Betweeners swapped rumors, some were convinced they were relaying scientific data from instruments measuring the encroachment, while others said the broadcasts were entirely personal, music or stories the operators felt like sharing, their purpose to bring in those lost in the encroachment. My own theory was that the broadcast material didn’t matter—it was the broadcasting itself that worked to hold back the encroachment.

The next two waystations were absolutely normal. When I asked the operators, they said they’d experienced nothing unusual. They returned what books, games, and recordings they’d loaned, we exchanged a bit of banter, and I successfully kept the fear from my face.

Waystation Dermal was the last waystation on my map. It wasn’t lost. It hadn’t stopped broadcasting. And yet, as I approached, my steps grew slower and beads of sweat sprouted all over my body. I couldn’t stop thinking about Toma asking me if I was still on the path. I was on the path. The stone was still under my feet. In training, betweeners were told that to leave the path outside of the limited confines of a waystation meant risking your life, but it had never been explained why the path protected us.

If the encroachment had moved so the path no longer threaded it or, worse, had collapsed entirely, how would I know? I stopped and closed my eyes. I tried to be aware of every part of my body. And yet nothing felt off, pressured, pinched, or stretched in that uncomfortable way that threatened the encroachment. But if I was already in the encroachment, would I know? Maybe it’s the difference between getting a little bit wet or being underwater entirely. I could’ve been in the encroachment for hours.

When I reached Waystation Dermal, nothing seemed out of the ordinary. The gate was closed, the doors to either side shut tight, and lights glowed from behind the windows. I knocked on the door. Gemma, the operator, was a woman who placed a great deal of weight on propriety. But when she didn’t respond to the knock, I went in anyway, a bag of supplies in hand as an offering. I desperately needed some normal, human contact.

Gemma wasn’t there, but the waystation was comfortably warm. A pot on the stove radiated heat, though the burner was off, and a tea bag rested in an empty cup on the counter. I filled the cup, leaving it to steep while I checked the right-hand side of the waystation. I found the radio on, and actively broadcasting, so I returned to the kitchen.

Waystation Dermal might be abandoned, but it didn’t feel abandoned. Unlike with Illia’s waystation, there was no sense of menace or strangeness, nothing off or missing. Except for Gemma, of course, but even so the waystation felt inhabited in a way that Illia’s hadn’t, as if Gemma would be back at any moment.

The radio from my cart chirped outside, but there was nothing to worry about here so no hurry to answer Toma. When the tea finished steeping, I added some cream and honey knowing Gemma wouldn’t mind, and held the mug between my hands, treasuring the familiar warmth, letting the steam wash over my face. I wandered around the kitchen, inspecting it in a way I never had before. The pictures on the wall looked familiar, and before I looked properly at each one I knew what I would see. Friends and family I had not hung out with in ages, but whose voices were so ingrained in memory I could’ve had entire conversations right then, knowing exactly how they’d respond to everything I’d say. A sudden longing for those lost times and places almost paralyzed me. My eyes filled with tears. How long had I been the operator here, and would I ever get to see those people again?

Something bit my thigh, and I yanked the clump of mud from my pocket, the surface smeared with my own blood. I felt another bite on my hand and dropped the mud, and stared at a ragged cut on my thumb. I looked up at the photos, now filled with strangers.

I didn’t know those people. I wasn’t Gemma.

Gemma wasn’t here.

I grabbed the mud and returned to my cart, holding the clump tight in my hand. It continued to gnaw at me, but the pain kept my mind clear. I switched the radio on.

“Toma, are you there?”

“Here. Your voice sounds strange. Are you okay?”

“I’m fine,” I said, my voice normal to my ears. “Waystation Dermal lost. Operator missing.”

“Understood.” Toma’s voice was tired, but unsurprised. And yet, she asked again, “Are you okay?”

“I’m fine,” I said, lying, because I didn’t know. “I’ve done my job, haven’t I?”

Toma paused. Her breathing was slow, cautious. “You haven’t done your job until you’ve returned to dispatch.”

She was right. Of course, she was right.

I breathed slowly, cautiously, then switched off the radio and parked the cart just outside the door for whatever operator came next. It wasn’t that far to the end of my route. I hurried down the stone path with the clump of mud in my hand. The encroachment pressed in, the edges of the stone path eroding into gray sand. A chorus of voices sang in my memory, my own and not my own and some I couldn’t be sure of. My right hand was a mass of pain, but it created a glow in me which made me feel more alive than I had in years, aware of every blade of grass and faint breeze as I walked, as if they were new and fresh and I’d never experienced anything like them before. Waystations were abandoned and operators were lost, but I had been found, and would remain found.

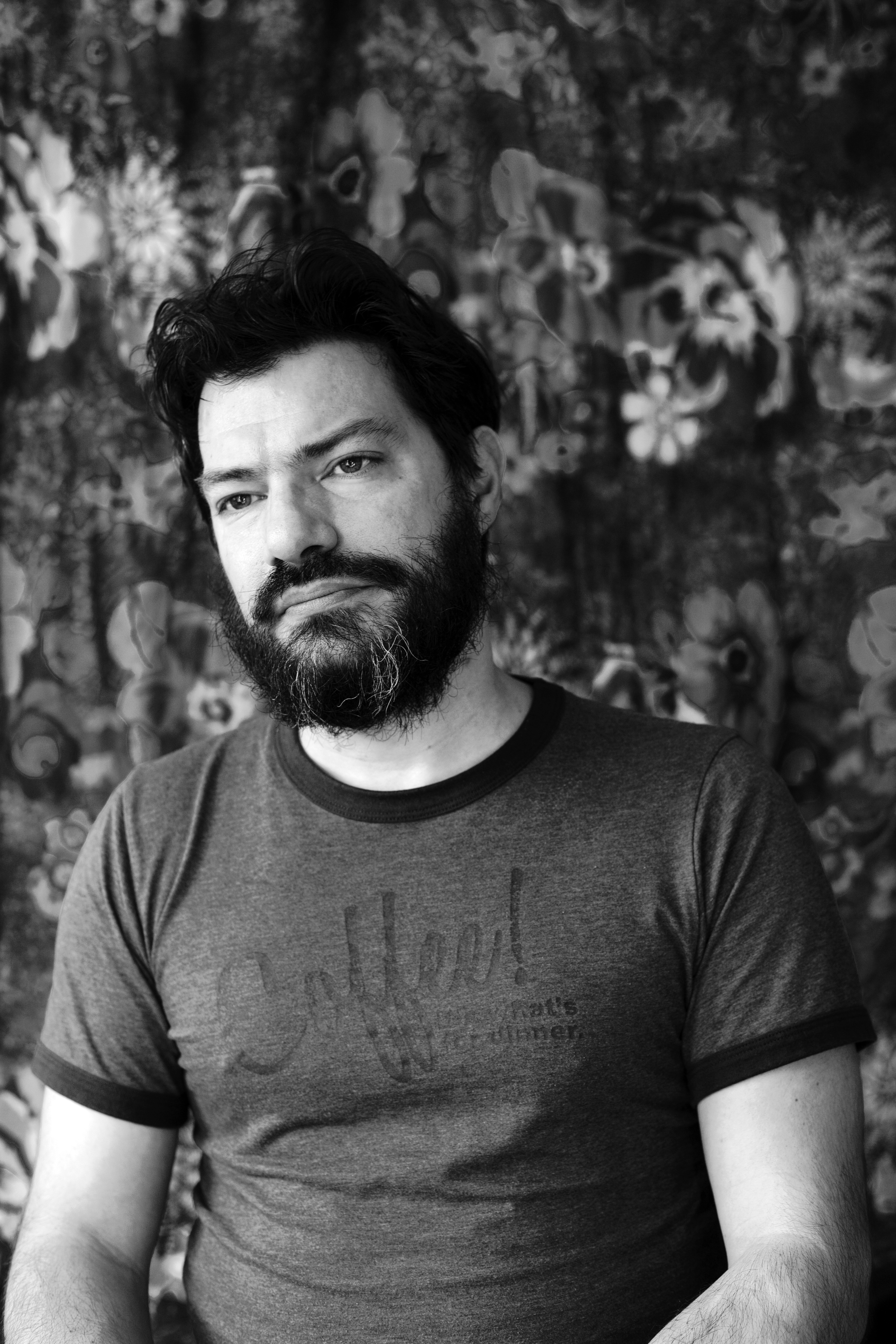

Andrew Kozma

Andrew Kozma’s fiction appears in Apex, Factor Four, and Analog, while his poems appear in Strange Horizons, The Deadlands, and Contemporary Verse 2. His first book of poems, City of Regret, won the Zone 3 First Book Award, and his second book, Orphanotrophia, was published in 2021 by Cobalt Press. You can find him on Bluesky at @thedrellum.bsky.social and visit his website at www.andrewkozma.net.