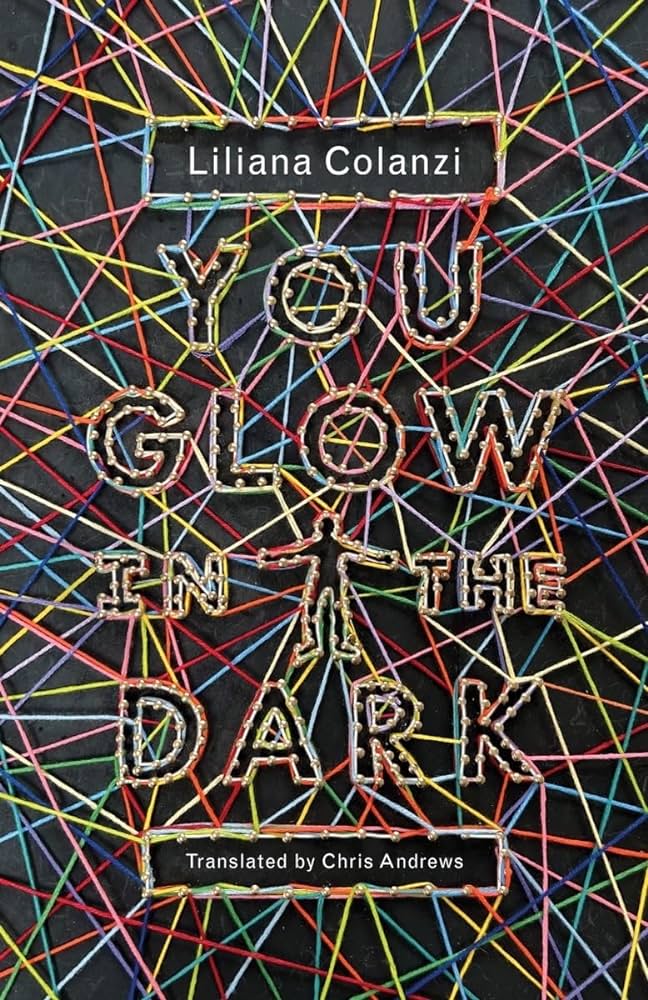

Cyberpunk is usually inextricably dualistic in its approach, most obviously in the dichotomy between cyberspace and meatspace, but also usually in its physical setting of the imperial core of the capitalist world-system; towering metropolises forcibly situating plenty and poverty side by side. In her superb new collection You Glow In The Dark, Liliana Colanzi excises half of the equation, situating the reader full within the periphery, applying cyberpunk’s political economy of precarity and reuse to people entirely disconnected from the shining future of cyberspace or the glittering towers of capital and prosperity. Inequality is a recurring theme, particularly in the form of environmental racism, anti-indigeneity, and misogyny. Taking place mostly in Colanzi’s native Bolivia, with one detour each to Mexico and Brazil, these are terse stories, often told in jumpy vignettes, with a dry, forceful voice (confidently captured by translator Chris Andrews).

The first and last stories of the volume, “The Cave” and “You Glow In The Dark” itself, are the two set outside of Bolivia. “The Cave” follows a Oaxacan cave throughout time, from prehistory to the distant future. The title story spirals around the real-life Goiânia accident in Brazil, a 1987 disaster in which medical radiotherapy material made its way into the black market as “little grains of fire,” killing four people and contaminating hundreds more. Both are about life and, more importantly, death, the sense of endings and the disruption of life cycles. In both, Colanzi ably decenters the narrative, avoiding (human) main characters, and achronological, jumping in and out of brief moments in time. “The Cave” opens the volume with an immediate, brutal visceral sense of the will to survive, with a prehistoric woman committing infanticide in order to avoid being slowed down.

“You Glow In The Dark” closes the book with a story more explicitly about the uncertainty of living on the periphery, with the desperate looting of a ruined hospital, abandoned by its investors, leading to widespread illness from the “light of the devil.” The thread of religion running through is a fascinating one, calling to mind a variety of Cold War era, pre-cyberpunk science fiction (Riddley Walker, The Canticle of Leibowitz, Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny’s compellingly flawed Deus Irae, etc) in the conflation of nuclear power and religion, barely-comprehensible, potentially-world-ending powers that they are.

“Atomito,” my favorite story in the collection, shares a preoccupation with radioactive saints, spectacle, and environmental racism in a poor neighborhood in the city of El Alto. It begins with the discovery of an “anomaly” in a colonial-era painting of the Virgin as a mountain (“which is how the indigenous painters managed to smuggle the worship of Pachamama in Christian iconography”), an almost-disconnected frame story that comes roaring back at the end to thematically seal the story. One of the most overtly cyberpunk-shaded pieces here, it follows a group of teens living in the shadow of widespread political disturbances, governmental crackdowns, and the literal shadow of a power plant, surrounded by “carcasses of fridges and old stoves stand like monoliths beneath the sky of the altiplano.” All of the castoffs of capital are here, but none of the decadent excesses. It’s a world barely extrapolated from our own – one boy’s precarious chicken-delivery job has been gamified (“MISSION ACCOMPLISHED – YONI HAS UNLOCKED THE NEXT STAGE”), and an electrical mishap at the plant creates not zombies but a meme-ified, viral communal dance. This is science fiction as a single step further into the unevenly distributed future, as William Gibson has (anecdotally) quipped.

“The Narrow Way” moves a bit farther afield, literalizing the colonialist relationship of the imperial core and periphery with a future religious colony in Bolivia. The titular cult, people with Germanic names who speak no “Bolivian,” are led by a reverend who insists that “the World Outside is made of darkness” while he pushes his flock to conquer nature (in the senses both of working the earth and of repressing their physical humanity). The commune is under his brutal patriarchal oppression, a theme which runs through many of Colanzi’s stories (who once said that the fantastic is “especially useful for talking about issues that have been repressed, but act as hidden or silent forces: indigenous history, fear of the other, feminine sexuality, the energy of the subconscious.”). It’s the most clearly science-fictional work of the seven stories, but even when Colanzi is riffing on more generic commonplaces – something called “metamaterial,” obedience collars inflicted upon the cult members, etc – she never over-explains them or loses focus on the human misery they’re enforcing. She maintains, in other words, the -punk in cyberpunk, the revolutionary dedication to the autonomy and humanity of the marginalized.

“Time is an illusion produced by the Devil,” the Narrow Way’s Reverend thunders, and whether set in the past, the present, or stretching into the future, a haunting Gothicism – the inescapable weight of the past weighing down on the present – imbues everything here. “The Cave” is the clearest expression of the small scale of human lives in relation to global time, but it saturates “Atomito” as well. “What will be left of this world two thousand years from now?” one teen wonders. “‘The mountains,’ her mother’s voice replies, clear as a bell.” A security pass for the power plant bears the image of the eighteenth century indigenous revolutionary Tupac Kamari but, in place of his traditional last words “I will return and I will be millions,” it reads “I will return and I will be neutrons.” Not even the revolutionaries of centuries past are safe from the vultures of (post)modern capitalism. “Chaco” also brings forward echoes of the history of colonialism when a white teenage serial killer absorbs the soul of one of his victims, an indigenous man, whose voice begins blending into the narrator’s stream of consciousness narrative in a rather experimental touch. It might be the most horrific story in a book full of them.

Much has been made of the new wave of Latin American gothic of recent years seeping into literary areas once occupied by magical realism, particularly that written by women–think Silvia Morena-Garcia, Mariana Enriquez, Samanta Schweblin, Monica Ojeda, etc–and rightfully so, given the remarkable work this movement has brought forth. Colanzi, indeed, is an academic whose work delves into this very movement, but on the strength of this book she deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as this vanguard of excellent writers. For a book barely surpassing a hundred pages, the weight of history bearing down on the reader is remarkably tangible and all-encompassing, a sense of darkness cloaking the distant neon lights of twenty-first century cyberpunk. As a hawker announces on the final page, drawing crowds to a radioactive survivor, “Open your eyes, ladies and gentlemen, what you are about to see is not for the fainthearted: the glow of death, the phosphorescence of sin, the man who shines in the darkness.”

Zachary Gillan

Zachary Gillan is a critic residing in Durham, North Carolina. He blogs infrequently at doomsdayer.wordpress.com and tweets somewhat more frequently at @robop_style. His reviews have appeared in Strange Horizons and Ancillary Review of Books, where he’s also an editor.