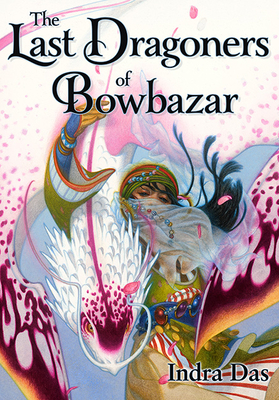

Indrapramit Das’s second book-length work, The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar, is a novella about a child growing up amidst dragons, set in Kolkata during the turn of the century—undated, except through references to films, video games, novels, and the barebones of immigration policies of the state—like the city of a bygone childhood, drawn with flourishes that make myth of memory. Like his recent fiction, Of All the New Yorks in the World, the fiction is localized, the city lingering under the fabrication (“Greenwich Village”, “Turkish” and “Ethiopian restaurants”, “Randall Island”) as its fertile foreground; in older short fiction, like The Moon for the Unborn, the city is where the characters return to mourn a disastrous adventure through space. The limits of the city are not trespassed in this novella, only built upon, each dragon circling its trademark Chinese restaurants and looking down at the Hoogly River. The Devourers, Das’s debut novel, allowed its characters more mobility through space and time, moving through peripheries like the Sunderbans, or the seventeenth-century histories of cities like old Delhi, but the narrative unmistakably returned to Kolkata as the site of transformation and love. The Last Dragoners is likely Das’s longest piece set entirely in the Kolkata of his own childhood, a city of familiar landmarks and atmospheric effects. The city is not only the setting, but the bounded limit of the narrative. Kolkata lingers and unmistakably creates the confines of Das’s literary worlds.

Reuel George, the protagonist whose life we follow through 120-odd pages, never leaves Kolkata, dispossessed of even envisioning a future outside it. The narrative covers his childhood living in the Bowbazar’s Dragoner’s Club, a fictional mansion that sets itself apart from the Calcutta Club, the Princeton Club, or the Dalhousie Club, colonial institutions for the British in the nineteenth century, and more in line with the Chinese social clubs in the city’s Chinatowns. The space is imagined as a community centre for migrants and not a hub of colonial enterprise. The house is a yellowing but once-affluent estate: “built by our ancestral settlers in the 1930s, with thick walls, three stories, palatial verandahs that wound around the structure.” I used to live in Kolkata in my early twenties, and have seen many houses like these. Their structure is a jumble of eighteenth and nineteenth century architectural styles, but to inhabitants of the city they appear coherent and intentional in their ruinous wealth—an emblem of the bhadralok culture that existed alongside and (perhaps because of it) also resisted colonial control. The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar, however, announces its allegiances with migrants from China and citizens from the northeast of India or Bihar, reclaiming a lost sense of heterogeneity in a city that is sharply proud of its regional culture. Reuel, or “Ru”, is a boy from nowhere, mistaken as one of the many Chinese migrants or a Nepali from India, who is out of place in a city of ethnic differences. “Everyone born on this earth has an ethnicity” Ru narrates. “It is, unfortunately, a signature left on our persons by god. That is to say, it is a signature left on us by our own hands …”

At school, Ru is bullied for his undefined features and inability to explain his heritage. Either parent has a different strategy; his mother tries to teach him about their nomadic legacy, determined to instill a sense of belonging—a citizen’s Indianness—accusing his bullies of having “narrow minds [that] cannot hold true places.” His father instead gives him legends and stories, explaining that they descend from Sir George, the saintly killer of dragons because there is an irony to the statement. In Ru’s hazy memories, he is served a feast of dragon flesh. In others, he watches his grandmother reveal a dragon. It is this elusive belonging between fictional narratives and a defiant belief in rights and liberties, between living inside an imagined mystical land and becoming part of a collectively imagined one, which forms the coming-of-age narrative in Dragoners. The novel follows Ru as he navigates school, makes friends, and falls in love in Kolkata; but the novel is about seeking, making, and forgetting ways to belong to the city. The backward glance of the prose-style is clever (Das uses it in most of his work), and Ru narrates the past through leaps of faith in his memory, the prose soaked in the narrative of the aftermath.

Das’s work has often been called magic realist for infusing his literary landscape with magic. I see it differently: the fantastic elements prop up the realist aspects, rather than the other way around, producing an array of symbols. The magical elements do not explain the realism, like superstitions are said to explain common-sensical beliefs, but render the landscape with a shimmering unknowability that avoids all explanation. There’s no magic system in the novella, but a lingering confusion—every night, Ru’s parents make him drink a potion that causes him to forget the magic he may have seen. Does Ru remember the burial of a dragon or its birth? Does Ru taste a sea-creature (an ethnic delicacy) or dragon’s flesh (an impossible magical being)? Aeroplanes in the sky are metallic beasts; flight on a dragon’s back produces the same strangeness of sitting in a flight’s window seat and looking below.

The novel’s ambiguous confessional style of writing infuses the city with secrecy and mystery, which creates the atmosphere of magic. Myth and legend are reinserted into a plausible world through Ru’s meandering narrative of his life. As Ursula LeGuin (who counts among Das’s influences) writes, myths show all that is not known, and cannot be expressed “except symbolically”; it is a narrative style that denaturalizes the assumed, the explainable, the empiricists natural system.

Kolkata is made anew through the symbolically rendered experiences of migrants. Das has long been invested in belonging and place, especially for those who live hyphenated and/or migratory lives of straddling different cultures, and especially in the heterogeneity of “Indianness”. This novella directly confronts the child’s subjectivity, and asks through a fantastic mode what it would mean if part of the child’s experiences were impossible according to the rules of nationality, ethnicity, citizenship, or even hyphenation. Or, simply, what if dragons were real? Belonging is difficult to come by when you do not remember and cannot retain memories. For Ru’s parent’s, who make him consume the “tea of forgetfulness”, belonging is even harder to come by when you’re uncertain about your child even believing those histories.

But, experienced through the hazy glow of magic, the narrative takes on an insightful bleakness, informed by the rules and language of the world which, secularized and/or standardized, no longer allows magic to shape and influence it. In the dragoners’ defense, they only wanted Ru to belong to the world he was born into—a normal boy in liberalized India. Early in the novella, Ru wonders whether it would be true to say that his parents gaslit him, hiding his culture from him, keeping him away from traditions that were very much alive for them. As the novel progresses, while a complicated family portrait is drawn, it isn’t explored far enough. Instead, the act of remembering, which is also the act of Ru telling this story, becomes the pivot of the tale.

Memory is entirely suffused with the anxiety and unreality of belonging one can never be certain of. Cultural memory is therefore kept at a distance, and so is its rich worldview. Ru tries various ways of remembering: reading science fiction and fantasy, grabbing at minute memories through exacting cinematic detail, or trying to refuse the noxious tea, and forms a sense of belonging through borrowed or stolen narratives. A dialogic subjecthood is formed: maintained between a personal historicizing through media and the continuity of sharing inheritance and traditions through family.

And, to my delight, The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar continues to be obsessed with the themes and methods of Das’s earlier work such as shapeshifting, birth and death, and most importantly, cannibalism—each of these themes revisited to consider identity and belonging. Some writers are unmistakably haunted, aware that their haunting must be negotiated and written, and Das puts these to the test with a Borghesian sensibility, embracing the inauthentic and ambiguous. Here, the dragoners consume the flesh of the drake/dragon, and alongside metaphors of serpents is the reigning motif: the ouroboros, the snake eating its own tail. Culture is both consumed and cannibalized, ritualized and inevitably lost, birthed and destroyed. Ru remembers through his forgetting. “I know now that forgetting and remembering was a cycle I have lived many times, a snake eating its tail.” Memory is merely a myth Ru holds on to. And so, the personal endures with all its adolescent angst and growing pains. Ru longs and yearns for selfhood that can contain both magic and reality. The anxiety of belonging to an impossibility is an ontological one, and perhaps that is why, even as the narrative ends with hope, it can never keep its grief and loss at bay. The loss of memory and magic endures through the cityscape. Some writers contain their haunting in their prose. Kolkata is, in all its modernity, a city bereft of dragons. Ru is, in all its bleakness, the last dragoner.

This is a narrative about how memory draws you in but also betrays you, about the difference between belief and truth, and about memory’s stake in creating reality. This is its greatest feat: by rendering all memory as shaky, the novel makes the possibility of dragons absolutely real. “Let it remain true,” the novel demands at the end, “Do you understand?”

Shinjini Dey

Shinjini Dey is a writer of long-form criticism and reviews of literary and speculative fiction. Her work has been published in Dilettante Army, Los Angeles Review of Books, Analog Science Fiction and Fact, Strange Horizons, and others. She won the Dream Foundry Writing Contest 2021. She also works as a freelance editor in the publishing industry and lives in Hyderabad, India. Find her on Twitter at @shinjini_dey.