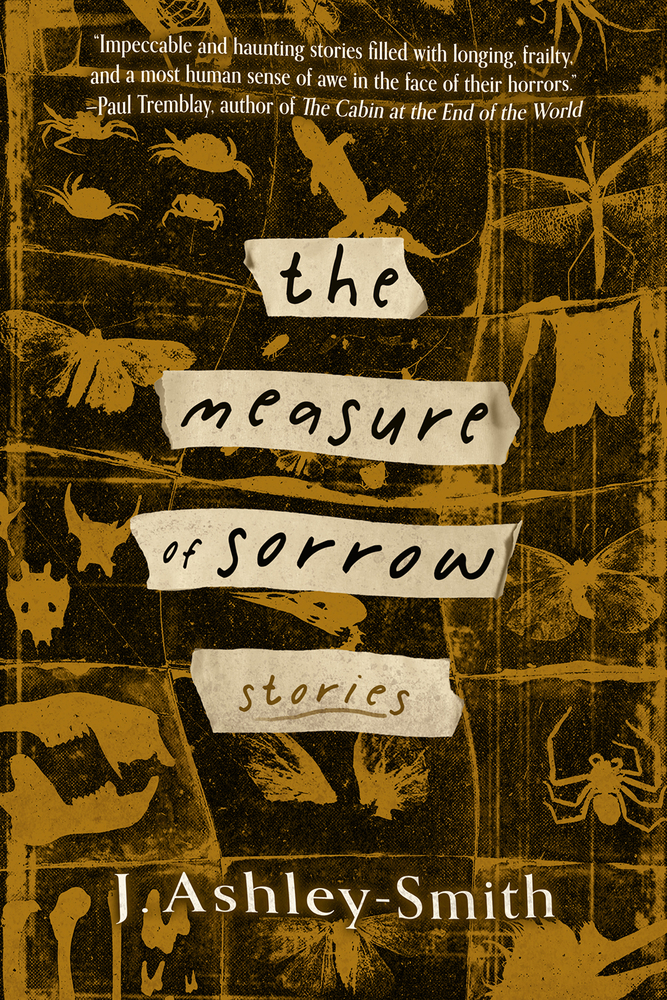

Some authors, even when dedicated overall to the art of unsettling their readers, pull their punches when it comes to horror stories about children. Not so J. Ashley-Smith, whose debut collection The Measure of Sorrow is full of parents and children lost in a world of darkness, grasping for meaning and connection, and often using the latter as a proxy for the helplessness of the human condition writ large. Throughout these ten stories Ashley-Smith exhibits a real gift for character and setting, adroitly situating readers in the headspace and isolating surroundings of his protagonists. Ironically, perhaps, given the overall incredibly bleak affect of the work, I found the actual rhetoric of his horror scenes somewhat less compelling, with the weird irruptions of the stories sometimes weakened in efficacy by cliche and vagueness.

My favorite work here, “The Family Madness,” is about a pair of siblings exiled to live with their uncle, possibly mad, after their mother, definitely mad, is institutionalized. It perfectly captures the exhaustion of the brother, the older of the two, whose life has been spent keeping his sister safe and nurtured in the face of the abuse and neglect of their parental figures. The flashbacks to their time with their mother are particularly effective, the unutterable horror of her manic episodes leaving the boy wishing his mother was dead – better that definitive horror than “this in-between place, this tangle of hope and despair.” The weird elements here – the uncle’s graphomanic “workshop,” the horrors opened up by his experiments, nicely linked to uncanny costumes and skins and puppeteering, thematically tying inner darknesses with outer appearance – are some of the strongest in the collection, but even here it almost feels like Ashley-Smith doesn’t fully commit:

“[t]he bits that Nathan had scribbled in English made no sense either. He referred often to “The Opus,” wrote as frequently of “The Opening” or “The Breach,” and peppered every note with magic-sounding hokum words like “The Beyond,” “The Umbral Prince,” or “The Wasting Shade.” It was gibberish, the ravings of a madman convinced of some inscrutable higher purpose.”

The names here fall a little flat, but more concerning, to me, is the preemptive dismissal of them as “magic-sounding hokum words.” It’s almost like the author himself doesn’t take them seriously, so the reader can’t be expected to either. What’s jarring is that he simultaneously fully commits to the inexorable nightmare logic of the narrative itself, doing nothing to soften the blow of a horror story centered on abandoned children. The narrative motion of “The Boon,” another favorite, is similar. A boy and his mother have just moved from a city to a small village, leaving the child isolated, lonely, and miserable – “[t]here was so little to do in the country. So little to distract him from that desolate, empty feeling.” This time, rather than the parental figure bringing harm to the child, it’s his peers, but the end result is much the same. Nature here literalizes the weird horror of the world, cut off from society and placed instead by an ominous forest that “might have been a cut in the world, an opening between earth and sky within which lay hidden movements and shadow.”

This is how nature presents in many of these stories, an isolating factor outside of city or suburban life; it’s perhaps telling that Ashley-Smith is a Brit long residing in Australia. In “The Family Madness” the children have moved from urban life with their mother to isolation with the uncle, in the collection’s titular novella we find a grieving father and son vacationing at an isolated farm, while “Old Growth” finds a divorced father driving into a forest, post-fire, with his distant, alienated children. The oppressing grotesquerie of nature reaches an extreme in “Our Last Meal,” a wonderfully spiteful post-breakup story about an asshole who finds kinship with the rats and leeches surrounding his ex’s family cabin in the jungle. “You’re draining the life from me,” his ex had said, while he continues to self-righteously protest that he had remade himself into “exactly what she needed” (her opinions to the contrary serve only to annoy him). It’s saturated with the kind of self-righteous disgust endemic to the narcissists of the world, and a strong example of the strength Ashley-Smith brings to his character work. The lack of a supernatural horror element means that he can render the abject horror of the predatory natural world perfectly.

The collection’s opener, “The Further Shore,” one of my favorites here, takes a more otherworldly approach to the isolating effects of nature in a Brian Evenson-esque absurdist epistemological collapse; civilization and perhaps reality itself left behind in favor of a beach haunted by vague night terrors, three men at a time populating a beach cabin and replaced, without memory, one by one as they die or vanish. As the opening salvo of the collection, it feels like a bit of misdirection in terms of setting with its unreality and lack of familial dynamics, but thematically prepares the reader for story after story questioning the utility of our search for meaning in the face of despair.

The isolation of nature also underlies “The Measure of Sorrow” itself, a novella which takes up a quarter of the book, and which unfortunately I found one of the less effective stories here. Centered on a father and son, united in a “grief that had no end” after losing their wife/mother, vacationing on a farm (which the son hates) whose ancient, haunted barn where “the storehouse of our minds is a living thing, bottomless and blind,” measuring our sorrows with the gap between darkest memories and public appearances. The narrative also bounces to italicized first-person flashbacks from the farm’s previous owner, who spent his childhood with a Nazi family in Germany, and the current owners, a woman in the final stages of pregnancy, and her depressive wife, the active farmer of the pair. The vagueness of the latter stands out starkly against the sharpness of the other characters, which undercuts her tragic narrative arc. In true Ashley-Smith fashion, in this story that features murderous Nazis, an evil genius loci, and a creepy barn, the most distressing scene involves the father and son yelling at one another. The barn, haunting and haunted but never effectively creepy or solid to this reader, feels almost incidental to all of the human dramas erupting around it.

For all that these stories have little to do with stereotypical Lovecraftian cosmic horror, the motivational fear at their root is the loss (or impossibility) of human connection in an indifferent universe. Ashley-Smith excels at the human touch, and if he strengthens the affect of the weird in his prose, already inherent in stories like “The Family Madness” and “The Further Shore”, he will be a writer to watch.

Zachary Gillan

Zachary Gillan is a critic residing in Durham, North Carolina. He blogs infrequently at doomsdayer.wordpress.com and tweets somewhat more frequently at @robop_style. His reviews have appeared in Strange Horizons and Ancillary Review of Books, where he’s also an editor.