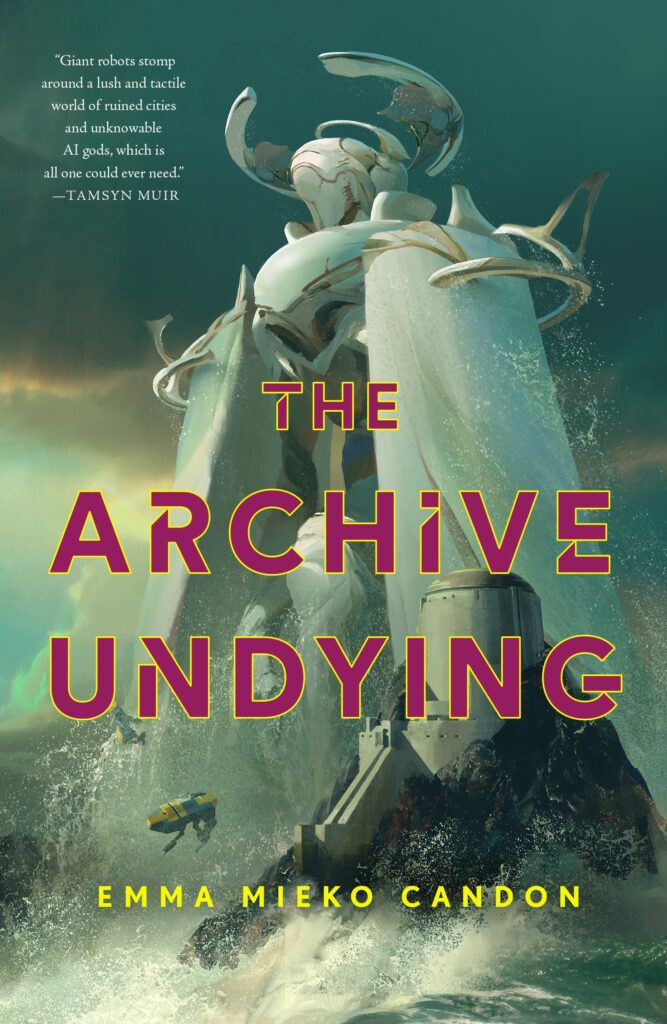

You might think, based on the cover (a giant robot) and promotional materials (“Giant robots stomp around” begins Tamsyn Muir’s blurb), that Emma Mieko Candon’s The Archive Undying is a novel for people who like giant robots. You’d be wrong. It’s a novel for people who like being confused.

This might sound like an insult, but it’s actually one of the highest compliments I can give a work of fiction. There’s not much I love more than being kept in the dark by a writer confident enough to treat their reader like an intelligent adult, but if you don’t like that sort of thing, this won’t be the sort of thing you like.

One of my pet peeves with modern mainstream SFF is the tendency toward prose work that reads as a barely-expanded screenplay, (“the first-draft-of-a-screenplay kind of novel that’s presently à la mode,” as Kai Ashante Wilson recently put it), foregrounding streams of dialogue (quippy and snarky, as often as not, which Candon does occasionally fall prey to) and barebones action over interiority or any interest in words or structural or technical craft. Candon does not have this problem – The Archive Undying is often an extended exercise in interiority, playing with unclear pronouns and shifting person and voice, varying chapter titling conventions and length, and blurred and mistaken identities, all to challenge and unsettle the reader. The prologue, to wit, is two and a half pages of collapsing boundaries between two characters (or the same character twice?), ending with:

“Where am I?” you hiss into the face that is yours, mine, ours. “What’s happening to me?”

I lean into your grasp, I touch my mouth to my mouth. Our mouths, together. I say “I,” and “I,” and “I-”

This is, in other words, a novel that is fully invested in being a novel, even as it’s one that wears its anime influences on its sleeve. There are, of course, giant robots stomping around here in some sort of science fantasy post-colonization world. The Archive Undying centers, mostly, on Sunai, a queer refugee and former relic of the defunct AI god of a destroyed city. This cycle, of human death and urban destruction and AI corruption, is endemic to the invented history of the novel, and Candon dives in full-bore into the possibilities inherent to this, blurring lines between human(s?) and AI god(s?), minds dissociated from bodies killed and rebuilt and rekindled and snuffed out again, chronologies melting as characters enter one another’s memories and dreams, narrative voices shifting from separate Greek chorus to more direct roles in the narrative, conversing or dueling or ignoring one another.

Candon’s preferred narrative motion is a jump forward followed by backfilling information (such as it is), all the while suffused with conversations built between characters rather than oriented toward reassuring the ignorant reader, a relatively uncommon sense of motion that put me in mind of nothing so much as Gene Wolfe’s Book of the Long Sun. Wolfe is, perhaps, the ne plus ultra of SFF designed to confound the reader, so he’s an obvious touchstone here, as are the more recent comparisons of the afore-mentioned Tamsyn Muir (Harrow the Ninth, in particular) and Kai Ashante Wilson’s novellas. Candon’s forward-and-back motion does pile up on itself to such a degree that the end of the book runs a very real risk of collapsing into absurdity as it cycles through so many double- and triple-crossings and impenetrable conversations and occlusions. It never quite falls, although it stumbles a few times, and it does start to feel somewhat stretched out and repetitious. Excessive length is another pet peeve of mine, although I know that for many SFF readers it’s a feature, not a bug, and the final revelations and resolutions here make it all feel worthwhile.

I was apprehensive going in that this is billed as the first volume of the Downworld Sequence, having very little patience for series these days, but fortunately there’s not a cliffhanger in sight – the narrative is pretty much wrapped up, and this book could comfortably be read as a standalone. Whether or not the sequel(s) branch off from the main narrative here or are similarly self-contained, they can comfortably occupy the setting, as this book devotes basically no time to trite worldbuilding exercises (another pet peeve of mine that Candon ably sidesteps). Historical details flit by in the background and current events believably pepper conversations, rendering them intriguing allusions and thematically-appropriate extensions rather than improbably-delivered history lessons. It’s telling that I’m not quite sure what “downworld” means exactly, even after finishing the book and knowing that it lends its name to the series as a whole (again, this is a good thing).

This book, which sidesteps or subverts so much of what I dislike about modern mainstream SFF, left me with pages of notes on themes to pull out, connections to draw, and items to pay attention to on re-reading the book (which the novel essentially demands you do): consent, agency, the tension between empathy/connection and the desire for solitude, bodies and boundaries and autonomy (it’s notable that the divine AIs here are Autonomous Intelligences, not Artificial ones) and their place in science fantasy in the long shadow of Frankenstein, trauma and healing, passive narration vs active agency. It feels a bit like a cop-out not to dig into those here, but it’s far more than can (or should) be covered in an initial review. If there’s any justice in the world, this book will draw obsessive readers together to pore over it and compare annotations and come up with a meta-text about what is happening in the book, why, and when. The Archive Undying deserves a fervent, attentive audience, and I hope it finds one.

Zachary Gillan

Zachary Gillan is a critic residing in Durham, North Carolina. He blogs infrequently at doomsdayer.wordpress.com and tweets somewhat more frequently at @robop_style. His reviews have appeared in Strange Horizons and Ancillary Review of Books, where he’s also an editor.