First off, massive congrats on your Bram Stoker and Shirley Jackson Award nominations! How have you found the experience of your work gaining this kind of attention and acclaim?

Thank you so much! My friend George was just asking me about this and it’s very, very surreal. I didn’t anticipate this. I had high hopes, y’know, but nothing like this. I’m not going to lie, I have found the experience to be both validating and intimidating. I’ve never wanted to be anything other than a writer, so this is a confirmation that I’m on the right track – that I’ve always been on the right track, even if there have been some pleasant and not so pleasant diversions along the way. At the same time, a critically acclaimed debut comes with a lot of pressure for what comes next. I worry that We Are Here to Hurt Each Other will be the only thing I ever write that’s worthwhile and that’s such a…messed up way to view things. I’m sharing it though because I always feel better knowing that even writers who seem to be ‘doing well’ are also struggling sometimes. NO WORRIES EVERYONE, I’M STILL INSECURE AS HELL. (Update: I won the Shirley Jackson Award for Short Fiction Collection! Trying to be less insecure!)

Before we dive into talking about your book, I listened to an interview you did recently where you talked briefly about the Convulsionnaires, a historical movement of people you described as ‘medieval cenobites’. Who the hell were these people and why are you so fascinated by them?

Oh my God, THE CONVULSIONNAIRES!. They weren’t medieval, I just don’t know historical time. So forgive me for that, especially CM Rosens, who is the podcaster I was speaking with when I mentioned the Convulsionnaires and is an actual scholar of the medieval and had to listen to my dumb blathering, bless her.

The Convulsionnaires were a sect of French Jansenist pilgrims in the late 1700s who visited the tomb of a deacon named Francois de Paris — whose ascetic lifestyle escalated to extreme poverty and self-flagellation. After his death some of the pilgrims visiting his tomb experienced convulsions which — according to them — healed them of various illnesses. The city closed the cemetery because the pilgrims were causing such a ruckus (and the Jansenists made the Jesuits super uncomfortable). So, they instead started having their convulsionary gatherings in the privacy of their own homes and salons and just as de Paris’ spiritual practices grew more severe, so too did the Convulsionnaires. They began to see the physical body as a site of corruption, sin, and malady and (strangely) that the convulsions they endured were curable by application of additional pain for the purpose of “release”. This relates back to the ascetic deacon de Paris because near the end of his life he took his vows of poverty and denial to the next level. He slept on a wooden trunk, used a sheet of iron hooks as a blanket, practised self-flagellation, and didn’t wear shoes so his feet were all cut up and damaged. He died at the age of 35 or 36 — though to be fair that was average for the time period — but I’m sure all that other shit didn’t help.

Anyway, the Convulsionnaires started beating and cutting each other for spiritual purposes and then they elevated to DIY crucifixion. “The self-mutilations and tortures the Convulsionnaires inflicted on their own bodies–they dismembered themselves, hurled themselves against walls, and drove nails through their skin— gave them pleasure…” (this is a quote from The Self and Its Pleasures: Bataille, Lacan, and the History of the Decentered Subject by Carolyn J. Dean). All that to say, I am fascinated by these people who seemed to torture themselves first in the name of God and then in the name of pleasure. I need to read more about them, I’m terribly curious about what some of their more severe antics were. The word ‘cenobite’ originally meant a member of a monastic religious order (ie. the Order of the Gash, as the cenobites from the novella The Hellbound Heart were known) and it seems that the Convulsionnaires were as close to real life Cenobites as they come.

The collection is called We Are Here to Hurt Each Other, and one of the things I liked about it was the sheer range of horror you explore. From body horror to weird and cosmic horror, and even a longer police procedural thriller type story. What connects all these stories together for you?

Thank you! What connects them for me is the idea that horror can come for you at any level. Physical, spiritual, mental, even the very stuff of reality isn’t safe. Nothing is safe. That is the core of horror to me and I think that’s what connects all of the stories. They are also connected by the idea of pain as transformative. Because nothing is safe, because we are constantly in danger; we are going to experience pain. It makes a perverse kind of sense then to try and ‘enjoy’ that pain or to at least put it to some kind of work. That transformation can be debilitating and it requires a lot in terms of sacrifice. But I think that’s a truth both sacred and profane: if you want something, it’s going to cost you.

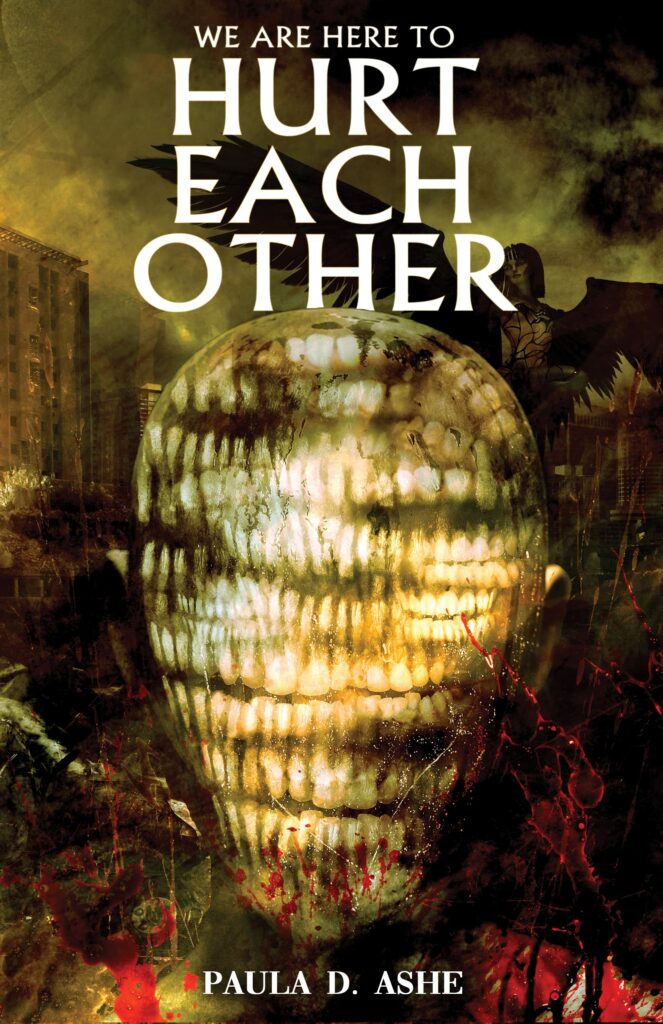

Do you have a particular fear of teeth? The cover of the book is fucking horrifying, and The Man with the Face of Teeth makes a gruesome appearance in a couple of the stories. What is it about the teeth?

I DO. Teeth are hideous and upsetting. I don’t like that they’re always wet (like bones but teeth are not bones, they are WORSE) and that they have nerves. I don’t like the liminality of the mouth and that revulsion is really concentrated in the teeth. I think what messed me up about teeth is that I have a diastema (gap) and as a kid I was made to feel very self conscious about it (I’m grown now and I like it), so I was always staring at other people’s teeth and orthodontia like a creep. The other thing is that before my daughter was born I saw an x-ray of an infant skull and saw that our faces are packed to the gills with teeth. There are so many goddamned teeth behind our faces when we’re born. It’s hideous. But then, the alternative (no teeth) is also gross. Soo…I write teeth-centric monsters because teeth upset me so much.

One of my favourite stories in the collection is “Exile in Extremis”. It’s a kind of modern epistolary story told through email and chatroom logs that still plays on some themes drawn from the classics. There are gothic references to grave robbing and R.W. Chambers’ The King in Yellow is mentioned directly in the story. Was this story a deliberately modern take on some classic gothic and weird tales?

It’s funny because obviously the Chambers/Yellow Mythos was intentional, but I didn’t think about the graverobbing aspect. Honestly I included it as a nod to the history of US hospitals graverobbing Black decedents in the 19th century. The backstory to “Exile in Extremis” is an old one (and relevant to that graverobbing bit) that will be expanded in a future project.

There’s a lot of fucked up and often abusive family dynamics in your stories and you’ve said in the past that “it’s difficult to view the world as a safe place when your first experience of the world is one where you weren’t safe”. How does that sentiment express itself in your fiction?

I think a lot of my fiction is about removing that illusion of safety, especially the illusion of safety that’s the result of some kind of privilege. I hope that people read my work and understand that the way people think about safety is very much influenced by those systemic qualities that so many folks like to pretend don’t matter. It may not seem so on the surface of a lot of my work — or maybe it does, I honestly don’t know — but I have been realizing in talking to folks (via interviews and podcasts and the like) how much my academic and activist backgrounds have influenced the stories I tell and how I tell them. Again I don’t think I make my work political, I just realize and understand how all work is political, how all art is about power, and manipulation (for lack of a better word) that is in service of the story.

It’s a tough thing to explore, especially given the old adage that ‘hurt people hurt people’ and your fiction goes to some really dark and upsetting places trying to grapple with that. How important is art that explores those dark places, especially in a cultural context of book bans and appeals for ‘positive representation’?

I think we have to have dark, transgressive, challenging art, because it serves as the antidote to the pabulum that gets passed for truth. The capitalist narratives that have shaped mainstream understandings of history are very often fomented by book bans and other political acts that get treated as harmless because they are (usually but not always) executed by suburban white moms. Book bans are orchestrated acts of cultural amnesia; you can tell because we keep having the same fucking arguments and the same fucking discourse about the same fucking shit (sorry, it upsets me). Are women even human? Should non-white people be allowed to do..anything? How dangerous are the trans? What if we just let the poors starve or die from horrible yet treatable illnesses? Why are the gays so gross? Are trees useful? Why can’t we charge people money to breathe? This is basic human shit and we could be living in a Star Trek-like society but instead we’re having actual arguments with politicians and their sycophants about why child labor laws exist and how we won’t get a second earth.

Horror and speculative work (at least the interesting stuff) is about how we move beyond antihuman/colonialism-drive ideas about society and civilization and humanity that have been literally taught to us (and so many generations before ours) in every way possible. Horror gives us the necessary space to critique what’s been handed to us as normal, privileged, and right. Sometimes horror can offer us alternatives. They aren’t always pretty, but they may be what’s needed.

There’s so much interesting, challenging work being produced in the independent and small press horror scene. Who are some of your favourite writers and publishers putting out the good stuff right now?

Yes! There are SO many presses doing incredible work; Brigid’s Gate Press (and very much looking forward to their imprint, Lady Mantis Books), also loving Medusa Haus, Apocalypse Party, Schism Press (if you haven’t read Vøidheads you have to read Vøidheads), Clash Books, Tenebrous Press, BLF Press (BLF stands for ‘black lesbian feminist), Nictitating Books, Weirdpunk Books, Grimscribe Press, Cursed Morsels, Castaigne Books..there are so many and I know I’ve forgotten many others. I also like to see what people have on itch.io and Big Cartel.

I hear you’ve got a new story coming out in a gross bug anthology put out by From Beyond Press. How gross is your gross bug story?

Man, I don’t know if I just didn’t make it clear enough in the story, but it’s about a lady who puts earwigs in her vagina because she misses her dead ex-girlfriend (among other things). Like, I’m not sure if there’s anything grosser.

What’s next for you? You’re an associate editor at Vastarien now, you’ve got two major award nominations, what are you working on and focussing on next?

I have a few more short stories heading for various anthologies (Book of Queer Saints Vol. 2 among others) but the main thing for this year are longer pieces; a couple of novellas and a novel. *gulp* Is this ambitious as hell? Yes. Will I likely not complete everything by year’s end? Probably. But I’ll have a lot of (hopefully) worthwhile stuff and that’s what I’m trying to focus on.

Massive congratulations for all the well-deserved praise We Are Here to Hurt Each Other has been getting, and thanks for being part of Seize The Press, this has been a genuine pleasure.

Thank you so much! It is absolutely unbelievable and I am constantly in a state of bewildered disbelief, mostly. Thank you so much for inviting me and thank you and your staff for all you do. Seize The Press is such a great and important magazine.

Paula D. Ashe

Paula D. Ashe (she/her) is an author of dark fiction. Her debut collection We Are Here to Hurt Each Other (Nictitating Books) was a Shirley Jackson Award winner for Single Author Collection and a Bram Stoker Award Finalist for Superior Achievement in a Fiction Collection. She is also an associate editor for Vastarien: A Literary Journal. She lives in the Midwest USA with her family.