Applying the capitalist ideology of endless growth to horror fiction, one might decide that hauntings need to be bigger. Instead of a house, detached and single-family, what if a high rise was haunted? What about an entire metropolis?

What if our whole way of life is haunted?

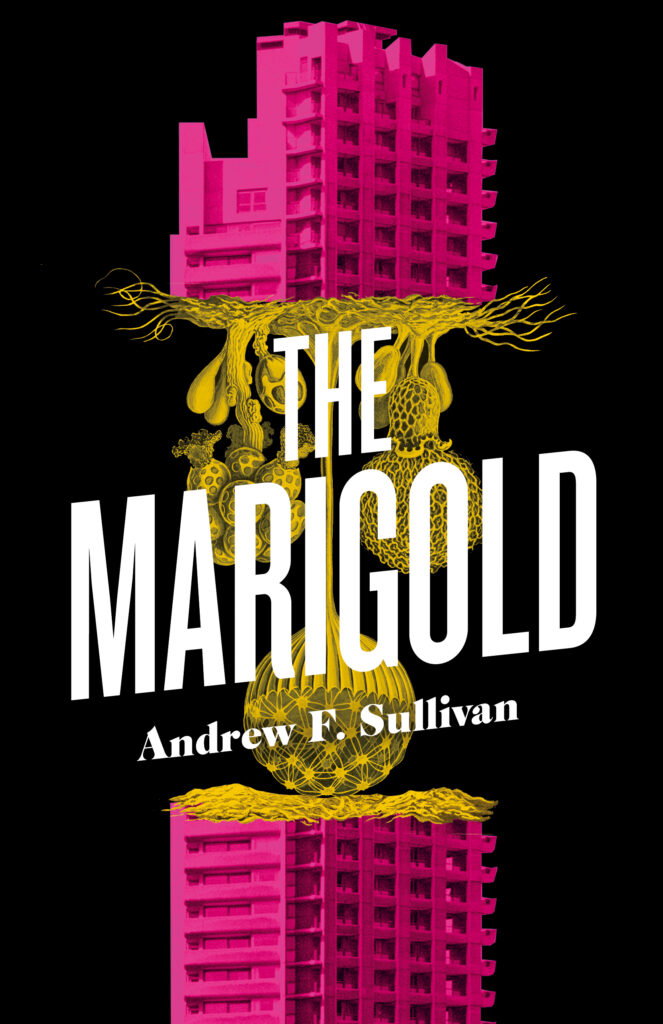

Andrew F. Sullivan’s The Marigold sets out to answer that question. It’s a bleak look at the price of endless growth, of meaningless luxury existing beside grinding poverty and precarity, of the rot and hunger underlying the capitalist metropolis in a world where everything gets worse, gradually and inexorably, everything going to feed the bottomless hunger of the shareholders and developers; an apocalyptic novel where “[t]here was no end of things, only an end of the self, a collapse barely worth mentioning.”

The Marigold is set in Toronto the day after tomorrow, beset by climate change, unfettered capitalism, and “the Wet,” a predacious black mold infesting some of the city’s newest and most opulent construction. Seeping through the dark spaces of the city and engulfing increasing numbers of its denizens, the Wet is a science fictional gloss on a ghost writ large, a hungry presence speaking in the voices of the dead to demand that debts be paid. It’s a literalization of capitalism’s endless growth and hunger and surveillance, but just as importantly, it’s a great monster, disgusting and enticing all at once. That’s The Marigold in a nutshell: it masterfully encompasses both trenchant social critique and excellent horror qua horror, dual approaches simultaneously integral to the novel while neither overshadows the other. All that is solid melts not into air, but into the rising waters of Lake Ontario, and the Wet must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.

Divided between four main point-of-view characters and interstitial chapters moving between various tenants of the eponymous building, The Marigold’s collective approach to narrative nicely decenters its story so that Sullivan can emphasize the Dickensian aspects of a rotting modern metropolis. The one-off point-of-views, titled by apartment number, are a particularly nice touch, little vignettes of disgust and apathy with the wealthy facing the emptiness of their investments while crossing paths with subletters and precariously-employed laborers, keeping the reader focused on the larger forces at play over the humans themselves. Following the darkest noir tradition, The Marigold’s characters find themselves powerless in the face of the systems constraining them, systems “so large they begin to defy human understanding” and growing ever larger and more alien. This pertains not only to capitalism and the Wet but to the real main character of the novel, the Marigold itself, Toronto’s newest and tallest high-rise, a monument to capitalist greed and hubris, a gold-plated piece of shit that began falling apart before construction was even finished.

The tower’s owner, Stanley Marigold, is one of the four POV characters, the one most clearly positioned as a villain, but Sullivan is too smart a writer not to humanize him. He’s a nasty, greedy bastard, but he’s as constrained by the world he was born into as everyone else is. The other three POV characters – a public health inspector, a rideshare driver, and a plucky adolescent – would seem to be more traditional hero candidates, but (again, in the noir tradition) things don’t quite work out that way. Faced with the rot, corruption, and haunting of modern life, dragged down by inertia and by ever-narrowing options, what can anyone on their own do?

This sense of inertia and glacial decline lies at the heart of the novel. Both the narrative and the slow apocalypse of the setting tend toward the static rather than the explosive – not a sudden, disastrous rupture but a steady yet almost imperceptible decline. The rot is already underlying the ideology of endless growth for the sake of growth, the true cost of perpetual consumption. What happens when the bill for (supposedly) endless growth comes due? “I bet you had a future once too,” one character taunts a recruiter nonsensically trying to interview him as the world dissolves around them. The Wet, the new totality of the city, begins repeating the mantra “No absence. Just presence.” as it grows through everything, a new life forcing its way through the concrete and debris of the city. It’s telling that outside of the Wet, the only lifeforms that seem to be thriving in Toronto are an increasing number of raccoons (a source of comic relief, to be sure, one of several excellent streaks of black humor running through the novel. I’m particularly fond of the running gag about the restaurants in the tower).

This slow-motion apocalypse carries through into the prose, Sullivan’s short, percussive sentences sometimes giving way to placid run-ons full of abrupt clauses piling up like things gone wrong in the Marigold, in Toronto, in the world: “You built a tower to outlast yourself. And so, what happened when those towers became burdens, when the Marigold empire was more rot than growth, ceilings collapsing on tenants and roofs leaking through the winter months, the mold growing so quickly you could trace it hour to hour, its hunger so similar to a human’s, its need to expand, to consume, to take over like looking in a mirror to find your basest impulses, the twitch in your eye before you struck your prey.” It’s a fantastic way to drag the reader into the mire, a static enumeration of miseries and disasters (and reader, there are a lot of miseries and disasters here).

In the end, what unites almost every character in The Marigold, every person living in Toronto, perhaps every person in the world, is their unasked-for collectivity in victimhood and hunger, a class consciousness born of paying a price no one asked for. It’s a dark kind of hope, but it’s what The Marigold has to offer. This is a bleak book for a bleak world, which is essentially what I, for one, am looking for in horror fiction: intelligent use of the aesthetic markers of the genre to tell an interesting story that reflects the haunted world we live in. As Bertolt Brech almost said, what is the haunting of a house compared to the haunting of capitalism?

Zachary Gillan

Zachary Gillan is a critic residing in Durham, North Carolina. He blogs infrequently at https://doomsdayer.wordpress.com/ and tweets somewhat more frequently at @robop_style. His reviews have appeared in Strange Horizons and Ancillary Review of Books, where he’s also an editor.